The Patient: The details of this patient’s complaints and presentation are lost, but we know he was a 66-year-old man who was being treated in the Emergency Department. His rhythm went from sinus tachycardia with non-respiratory sinus arrhythmia to multi-focal atrial tachycardia (MAT) to wide-complex tachycardia. The WCT lasted a few minutes and spontaneously converted to an irregular sinus rhythm.

Wide-complex tachycardia: Ventricular tachycardia or aberrantly-conducted supraventricular tachycardia? When confronted with a wide-complex tachycardia, it can be very difficult to determine whether the rhythm is ventricular or supraventricular with aberrant conduction, such as bundle branch block. The patient’s history and presentation may offer clues. It is very important, if the patient’s hemodynamic status is at all compromised (they are “symptomatic”), the WCT should be treated as VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA until proven otherwise.

There have been many lists made of the ECG features that favor a diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia. Here are two such lists: Life In The Fast Lane, and National Institute of Health.

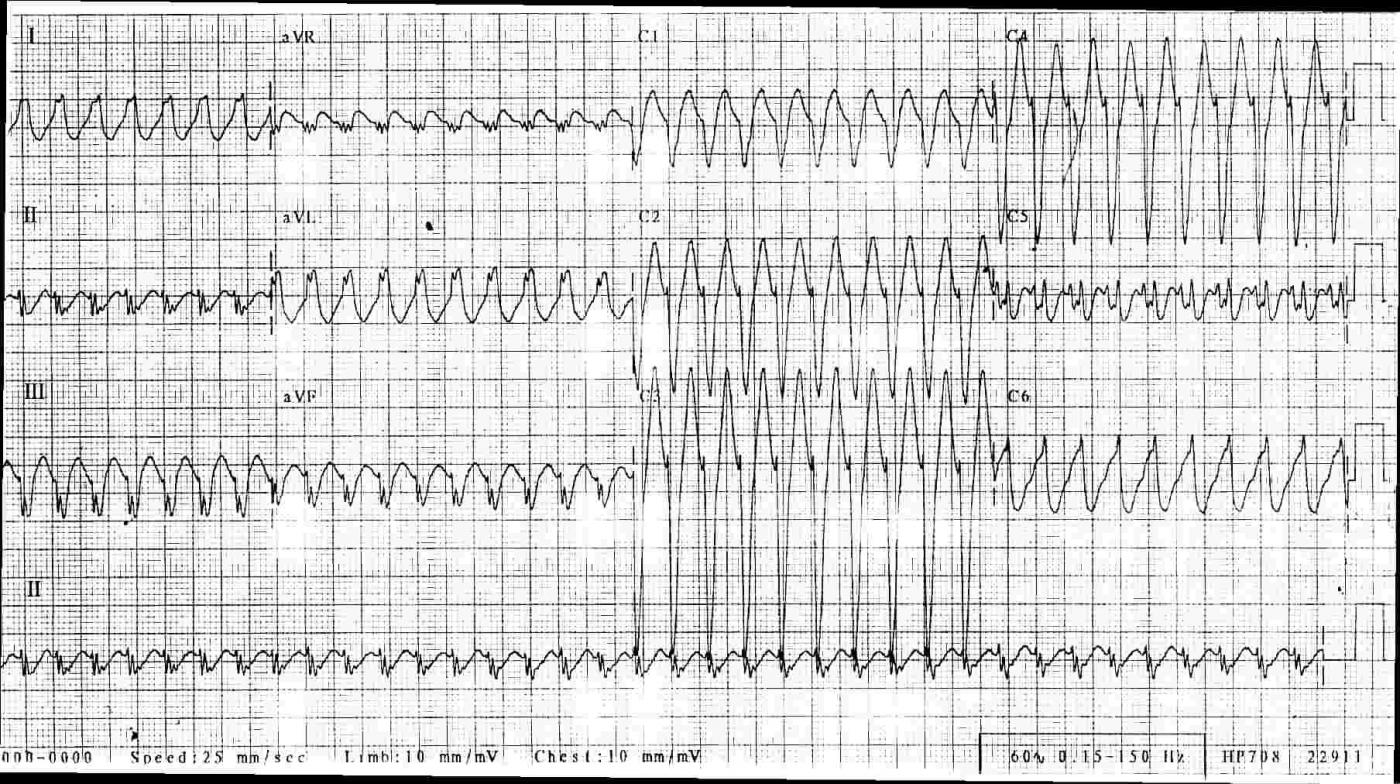

The ECG: This ECG shows a regular, fast, wide-QRS rhythm. The rate is 233 bpm. It had a sudden onset and sudden offset (not shown on this ECG), and the rhythm lasted about 3-5 minutes. The patient felt the change in rate, but did not become hypotensive or unstable. Some features that relate directly to the most commonly-referenced VT vs. SVT charts are:

1) The morphology of the QRS complexes in this ECG is indicative of left bundle branch block. V1 has a wide, negative, monomorphic QRS. Leads I and V6 have wide, positive QRSs. Aberrant conduction often takes a LBBB or RBBB pattern.

2) The QRS is difficult to measure due to unclear start and stop points in all leads, but the overall width appears to be about 120 ms (.12 sec). VT tends to have very wide QRS complexes, greater than 160 ms.

3) This ECG’s axis is about -30 degrees, and aVR is negative. This indicates an axis just a little to the left, within normal range. An extremely abnormal axis, between +180 degrees and -90 degrees (called Northwest axis) almost always indicates VT. Both SVT and VT can have normal axes.

4) The precordial leads V2 through V6 have RS patterns. Any precordial lead havig an RS pattern favors the diagnosis of SVT.

5) The precordial leads transition from negative in V1 to positive in V6, with a somewhat late transition in V5. Precordial concordance (all precordial QRS complexes in the same direction) favors the diagnosis of VT. A negative QRS in V6 also favors the diagnosis of VT.

6) I see no AV dissociation (P waves that are not associated with the QRS complexes). If present, AV dissociation guarantees a diagnosis of VT.

While the actual differentiation between SVT and VT can be much more complicated than this, I feel that this patient has a very good chance of having SVT with LBBB that is probably rate-related. His rhythm spontaneously converted to an irregular sinus rhythm. If this tachycardia recurs or persists, an electrophysiological study could be needed to find the cause and confirm the diagnosis.

I would love to know what you think about this rhythm. In the Basic Rhythms section, I will post a strip of his multifocal atrial tachycardia.

All our content is FREE & COPYRIGHT FREE for non-commercial use

Please be courteous and leave any watermark or author attribution on content you reproduce.

Comments

A Regular WCT — My Hunch = SVT + LBBB

One of the most common and important diagnostic distinctions in emergency medicine involves assessment of regular WCT (Wide-Complex Tachycardia) rhythms. I’ve been fascinated by this subject for years — so I’ll add to the sources Dawn provides, My ECG Blog #42 — in which I present a user-friendly approach that has served me well over the years, and which with practice provides a high-likelihood assessment of the regular WCT within seconds.

Dawn has already covered the major diagnostic parameters to assess. To this, I’ll add the following comments.

As per Dawn — assessment of hemodynamic stability is KEY. If the patient is not hemodynamically stable — then it no longer matters whether the rhythm is VT or SVT with either preexisting BBB or aberrant conduction, since treatment is the same = immediate cardioversion! We are told that the patient in this case was and remained hemodynamically stable for the brief period of time that the rhythm lasted. Once you’ve ensured that your patient is stable — then, by definition — you have a moment of time to contemplate the rhythm (ie, even if the rhythm turns out to be VT — immediate cardioversion is not necessarily needed if the patient is hemodynamically stable).

I begin my assessment by describing the rhythm. As per Dawn — there is a regular WCT rhythm at ~230/minute, without clear sign of atrial activity. At this point — it is well to consider statistical likelihoods. There is literature showing that at least 80-90% of all regular WCT rhythms without atrial activity will turn out to be VT (especially if the patient is older and has a history of underlying heart disease). It should be emphasized that >80-90% likelihood is not 100% likelihood — but this very high probability that the WCT is VT does mean that we need to prove that the rhythm is not VT, rather than the other way around!

All of this said — I suspect the rhythm in this case is not VT. For time-efficiency — I’ll not review all of the features I cover in Blog #42. Instead I’ll focus on that feature I feel most relevant to this case = Does QRS morphology during the WCT resemble any known pattern of BBB? The answer in this case is YES. Predominant negativity of the QRS complex in anterior leads — in association with an all upright QRS in lateral leads (as seen in this tracing) — is perfectly consistent with LBBB. But the principal reason I strongly suspect a supraventricular etiology in this case — is how short-lived (ie, narrow) the initial small r wave in leads V2, V3 and V4 is. This is followed by an extremely steep S wave downslope that very rapidly attains its nadir (lowest point). Supraventricular rhythms tend to have a more rapid initial deflection — because, with the exception of WPW — the electrical impulse is transmitted over the specialized conduction system. In contrast, ventricular rhythms tend to have a significantly slower initial deflection — because they originate from the ventricles and away from the conduction system.

BOTTOM LINE: It’s often impossible to attain 100% certainty as to the etiology of a regular WCT rhythm from a single initial tracing. Use of QRS morphology has its limitations. Exceptions clearly exist. For example — a patient with severe underlying heart disease may have a markedly abnormal-looking wide baseline QRS morphology that does not resemble any form of BBB. If such a patient develops a reentry SVT without sign of atrial activity — the rhythm will look like VT. As a result — the clinical reality is that one often needs to initiate treatment before knowing for certain the etiology of a WCT rhythm. In this case, even though I would not be 100% certain — the extremely narrow initial r wave deflection in leads V2, V3 and V4, with very steep S wave descent looks typical enough to me of an SVT rhythm — that I’d be comfortable with initial trial of adenosine or other AV nodal blocker on my hunch that the rhythm is supraventricular. I’d do so being ever ready to immediately cardiovert if at any time during the treatment process the patient became unstable.

Ken Grauer, MD www.kg-ekgpress.com [email protected]

Diagnosis or a Decision?

Thanks again, Dawn, for a great case. You gave a very good analysis of the ECG though I do have something to say about one of your comments.

Ken - an excellent discussion also but again, I have a comment to add.

Let me get to the point quickly: I don't know what this is! Some aspects point strongly to SVT with aberrancy but other aspects really cause me to question that diagnosis.

First, Dawn. You mentioned that an rS complex (or RS complex) in a precordial lead "favors" SVT - but it really doesn't. The basis of this finding was first mentioned in the Brugada article in the 1990's which stated that ALL the cases of SVT with aberrancy had at least one lead with an rS (or RS) complex but so did about 80% of the cases of VT. Only about 20% of the VT cases had no rS or Rs complex in the precordial leads. My own personal experience tells me that it is probably fewer than that, though I have never done a study. So its presence doesn't really help us either way; only the complete absence of rS or RS complexes helps and especially if it is negatively concordant.

Ken, I understand what you are saying about the narrow r waves and the smooth, straight downslope of the S waves in the precordial leads. That is a feature that I look for and use quite frequently; however, I have seen several documented VTs with exactly the same appearance. In each one I was very sure that it was an SVT with aberrancy, but I was wrong. So this morphological attribute - while helpful - is not really diagnostic (and, granted, you never claimed that it was).

Now what concerns me about immediately declaring this WCT as an SVT with aberrancy? It's in the history and some other findings. This is a 66 y/o man that has an ECG done in a hospital setting (ER). He also had an episode of multifocal atrial tachycardia (MAT). This tells me that he was very ill, likely with severe acute and chronic respiratory problems and perhaps other co-morbidities. Healthy people don't get MAT. In theory it can be seen in digitoxicity and a few other things, but in my experience it has always been in patients with acute exacerbations of chronic pulmonary problems - usually along with a number of other co-morbidities. I just find it very unusual that a 66 y/o man with all these health problems suddenly develops an SVT at a rate of 230/minute. AVNRT is usually around 160 - 180. As we now know, AVNRT circuits occur either in the AV node or in parts of the atrium proximal to (and usually including part of) the AV node. At any rate, the impulse has to conduct at least partly (if not completely) through the AV node. If you put this man on an exercise bike and revved it up to warp speed, I doubt seriously that one could get his AV node to conduct to a ventricular rate up that high! Maybe if you injected him with about a ml of 1:1000 epinephrine. The only patients in whom I have seen a rate of 230 (or about) due to an AVNRT have been in young women from their late teens to early twenties. And even then, I think the highest was 220/minute and that was in a young woman who was otherwise very healthy! That makes me think in terms of an infrahisian rhythm. If he were so ill that he developed MAT, I don't think he would be very likely to develop an atrial tachycardia that fast and, even if he DID, I doubt that his AV node could conduct the impulses at a rate of 230/min at his age without 2:1 or Wenckebach conduction.

The other thing that bothers me is the notching or slurring in the upstroke of the S waves in V1. While the QRS in V1 otherwise appears rather classic for cLBBB, the QRS in V6 does not. There is an inverted T wave that does NOT look like a repolarization abnormality. Also, the QRS complexes in Leads II, III and aVF appear somewhat fractionated to me. Granted, both V1 and V6 should have atypical QRS complexes to qualify as VT. However, the other findings are very suggestive of an old scar - likely due to a previous MI or perhaps some other process - which would provide an excellent substrate for a reentrant VT.

The WCT lasted only a few minutes. Usually the short, non-sustained VTs originate in the outflow tracts and are benign. As you can see, if this is VT it would be originating in the right ventricular apex (and "nothing good comes out of the apex"). Most malignant monomorphic VTs aren't so short, but they can be.

Again, I don't know what this WCT represents but I suppose I would lean a little bit toward VT.

Regarding treatment, we all agree that there is no point trying to interpret a WCT if the patient is unstable - cardiovert immediately!

In my classes, I ask my students these questions: "If you treat a WCT as a VT and it turns out that it was actually an SVT - what have you just done?" The answer is: "You have just treated an SVT!" However, "If you treat a WCT as an SVT and it turns out that it was actually a VT - what have you just done?" The answer is: "You have either killed or risked killing the patient!"

Sometimes we are fortunate enough to make a DIAGNOSIS; other times we are forced to make a DECISION.

Thanks, Dawn, for providing this excellent forum for discussion and learning and thank you, Ken, for playing "electrocardiographical tennis" with me. Stay safe, everyone.

Jerry W. Jones MD FACEP FAAEM

https://www.medicusofhouston.com

Twitter: @jwjmd

Great discussion!

Thanks, Dr. Jones, for making this discussion even more lively! I do see your points, definitely. I ALWAYS teach to treat WCT as V Tach until PROVEN otherwise. I know Dr. Grauer does too. One big problem is that I do not remember this patient any more. I have so many ECGs in my collection from when I was working in a very fast-paced busy Emergency Department. I saved ECGs, and always thought I would remember the details, but then I didn't. How I wish I knew the full story of this patient. For me, WCT is fascinating, but from a purely clinical standpoint, I never wasted time trying to figure out whether the rhythm was SVT or VT. I did my best to weed out the SINUS tachs with aberrant conduction, as I would NOT want to treat that as VT. I also saw cases of atrial fibrillation with BBB treated as VT a few times in my career - with no harm to the patients, just a delay in getting to more appropriate treatment. Since Ii am a nurse, the treatment choices were mine only for a few minutes, then would be taken over by the ERP.

I hope I did not mislead anyone that an ECG like this is EASY to interpret - my final diagnosis was just my best guess. Of course, an EP study would be great!

Anyway, both you and Dr. Grauer gave me a lot more to think about, and I'm not afraid to say - I'm not sure what this is. Thank you both so much.

Dawn Altman, Admin

Thanks, Dawn!

I saw on your LinkedIn post that someone had written "Easy! It's SVT with LBBB." I thought, "If you think this is EASY, then you need to learn a lot more about ECG interpretation!"

I have the same problem re: the ECG collection. I didn't even try to save any ECGs throughout my career. It was only when retirement was less than a year away that I began having nurses, techs and my associates save as many ECGs as possible. Of course, very few had any history or outcome attached.

Jerry W. Jones MD FACEP FAAEM

https://www.medicusofhouston.com

Twitter: @jwjmd